Tropical Siesta

2017

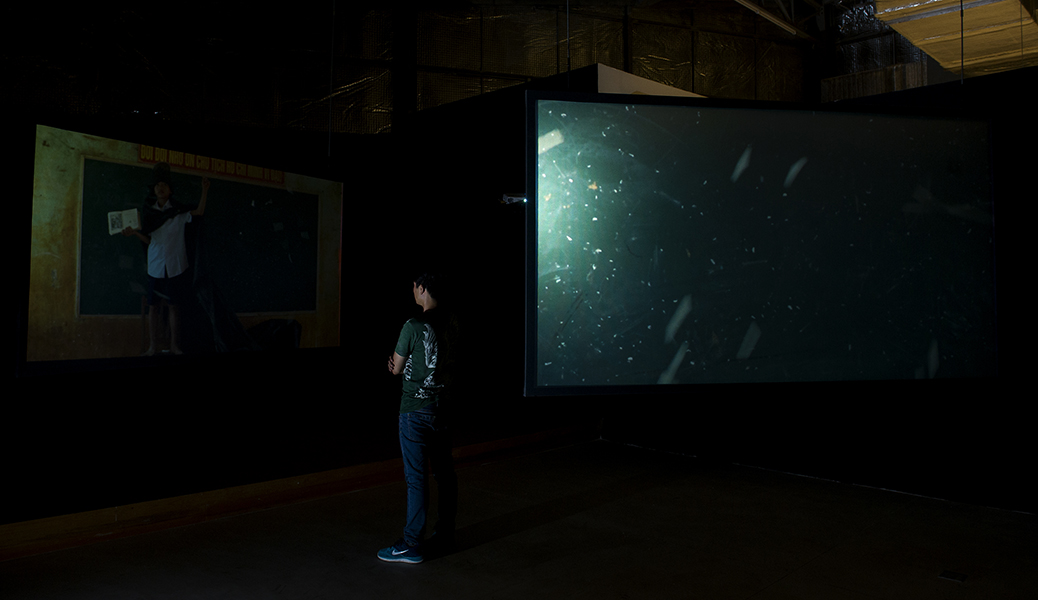

Double-channel synchronised video

13:41 mins (loop), HD, colour, sound

‘Tropical Siesta’ begins with a tranquil landscape of rice paddies in rural Vietnam, where children are profiled carrying farming tools, an agricultural community whose only building given presence is a dusty and derelict primary school. Painted images of school children soon appear hovering over the wooden desks of a classroom, these animated figures eventually giving way to real yawning boys and girls, their unusual ‘beds’ seemingly not hampering the daytime snooze that pervades. A story is narrated in subtitle, below these panned out frames, which begins:

‘Vietnam. The Present. After years of independence and performing seclusion policy, the government has successfully realized agriculture as central to the nation’s economy. Everyone is a farmer. Time is frozen in endless tranquil rice paddies. Children live in communes and work in self-sufficient farming communities. In the commune there is a school named ‘Alexander de Rhodes’. With no adults around, the children design their own study curriculum. The children take stories from the ‘History of the Kingdom of Tonkin’, written in 1651, to reenact a make-believe game. Rhode’s books are the only texts the children study, all other memories being locked away in a library, hidden in a hexagonal maze, its key and location are lost. The children transform and manipulate the content of he stories for their own interest. For them, this make-believe is something that brightens up their agricultural daily life….’

What follows are the children’s make-believe, where tales of ‘About Crime and Punishment’ and the ‘Water Goddess’ are ‘performed’. In the first, the children make fun of de Rhodes observation of 17th century punishment methods in Vietnam, where he recalls prisoners are not provided food and so must beg in the general community with their necks shackled in a wooden device. In their ‘performance’, the children choose a ladder as their shackle, each space between the rungs restricting room for one. They march single file across the mud walls of tilled fields of rice, moving (at times naked) within the narrow waterways that enable their agricultural life. In the latter ‘make-believe’, Rhodes recounts the myth of ‘Queens Gate’, an oral traditional tale of the worship for a Chinese princess who drowned by her father’s hand due to her notorious lifestyle, her corpse found in the river serendipitously with a local villager who had also died and they were thus buried together at the port, now called ‘Queens Gate’. In Phan’s re-telling, her sea-goddess heroine initially lies eyes open, dressed in royal costume, amidst a running stream. Her ‘local villager’ is not found robed in dignity as she, but rather naked and levered to land by sharp metal hooks, his face never revealed.

At times, Phan’s lens recalls the ethnographic film work of Timothy Asch in style and method (textual narration; long profile shots of children, naked, looking directly into the camera), while the imaging of the relationship between subject and landscape lingers like the ghost-like, rural hauntings of Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Phan’s attention to light and sound is particularly compelling here). In much of this filmic imagery Phan poses a challenge to the visual association of stillness with death (the young goddess lying still in a pool of water); of posture with power (the child dressed in the likeness of the printed image of de Rhodes in Christian garb carrying a book and pointing to the heavens); of rural life with innocence (children taunting death rituals in the countryside). In Phan’s filmic world there is revelry in a landscape dominated by

the natural elements, but it is an environment that appears lacking any historical sense of purpose in time, this little community entirely cut off from knowledge of its past. Purpose is instead experienced within their ‘tropical siesta’, which is where the play of these children redeems their historical ignorance, reflected in the large sculptural flower sculptures that light up their dreams, their nights. These dazzling sunflowers recall the celebrations of the Vietnamese New Lunar Year, these lights symbolizing rebirth and fortune, typically found in the central boulevard of urban cities across the country.

The landscape of ‘Tropical Siesta’ speaks to the dark eras of Vietnamese history where the country has economically and ideologically struggled. For example, in North Vietnam in the 1950s, the Vietnamese Communist government sought to eradicate private ownership of land, commerce and trade with the view to improve agricultural production alongside collective principles (which saw many landlord class executed) - a land reform practice consequently attempted in South Vietnam during, and following, the Vietnam War. Today this traumatic history, which saw thousands lose their dignity and livelihood remains politically sensitive and un-reconciled, thus not published or taught within national educational curricula. In Phan’s poetic amnesia we are given a window onto that forbidden landscape, though its gaze is a historical fiction, nuanced in fact discovered in foreign archive, strewn together by the perception of innocence in childhood. Compelled by the question of truth in a Vietnamese cultural landscape mired by political agenda and social consumer apathy, Phan approaches her art like a magician might weave between science and superstition, between logic and illusion. Both artist and magician possess a common motivation to uphold the myth of their actions, they are the court jesters of the contemporary world, responsible for pointing the finger at shame, complicity or greed whilst also offering reprieve or atonement. Roland Barthes states ‘myth is a type of speech’, going further he elaborates ‘Ancient or not, mythology can only have an historical foundation, for myth is a type of speech chosen by history; it cannot possibly evolve from the ‘nature’ of things’. Speech of this kind is a message. It is therefore by no means confined to oral speech. It can consist of modes of writing or of representations; not only written discourse, but also photography, cinema, reporting, sport, shows, publicity, all these can serve as a support to mythical speech’.[i] For Phan Thao Nguyen, her message is rather a question – how are our imaginations of a different present informed if our myths are denied reinterpretation and our archives non-existent? What would happen to our humanity if we had forgotten how to recognize our prior dreams and fears?

Excerpt from curatorial essay by © Zoe Butt