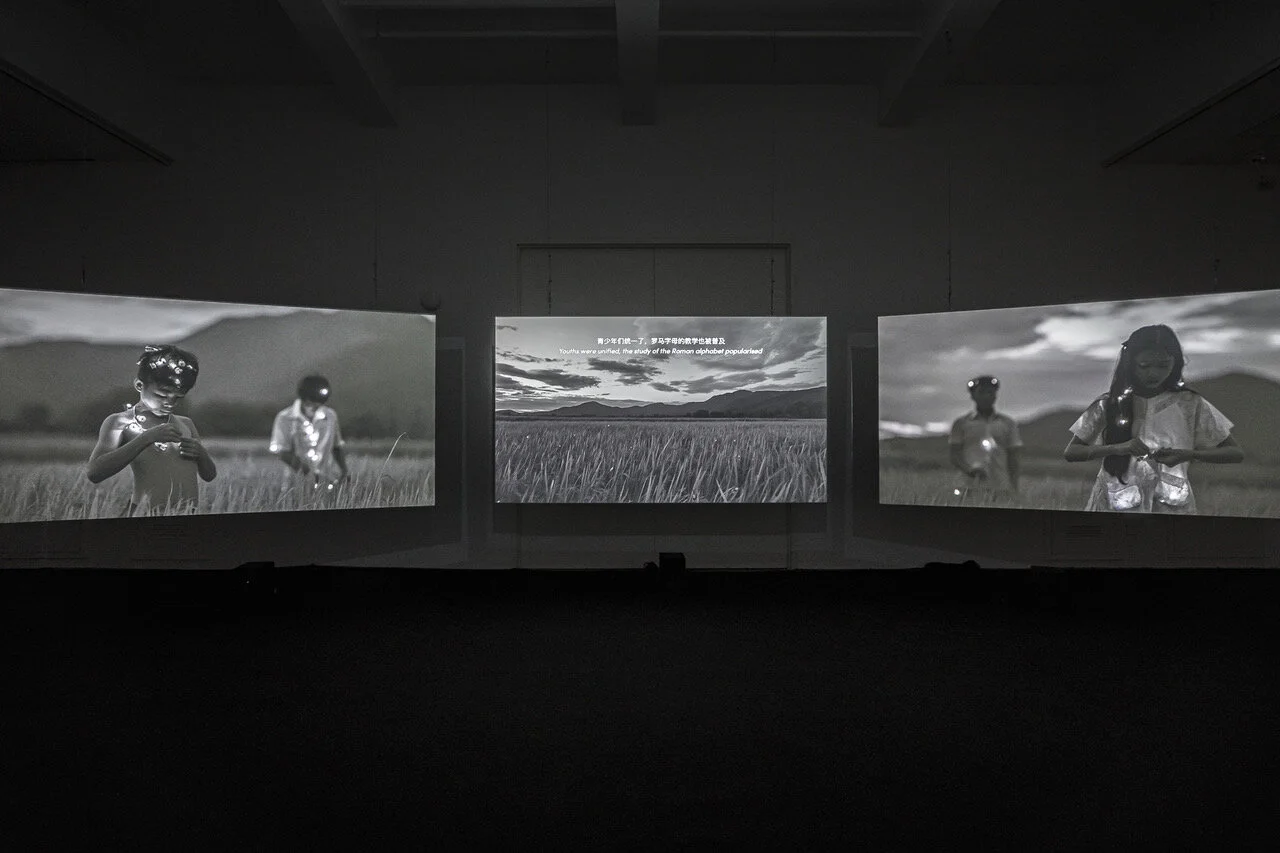

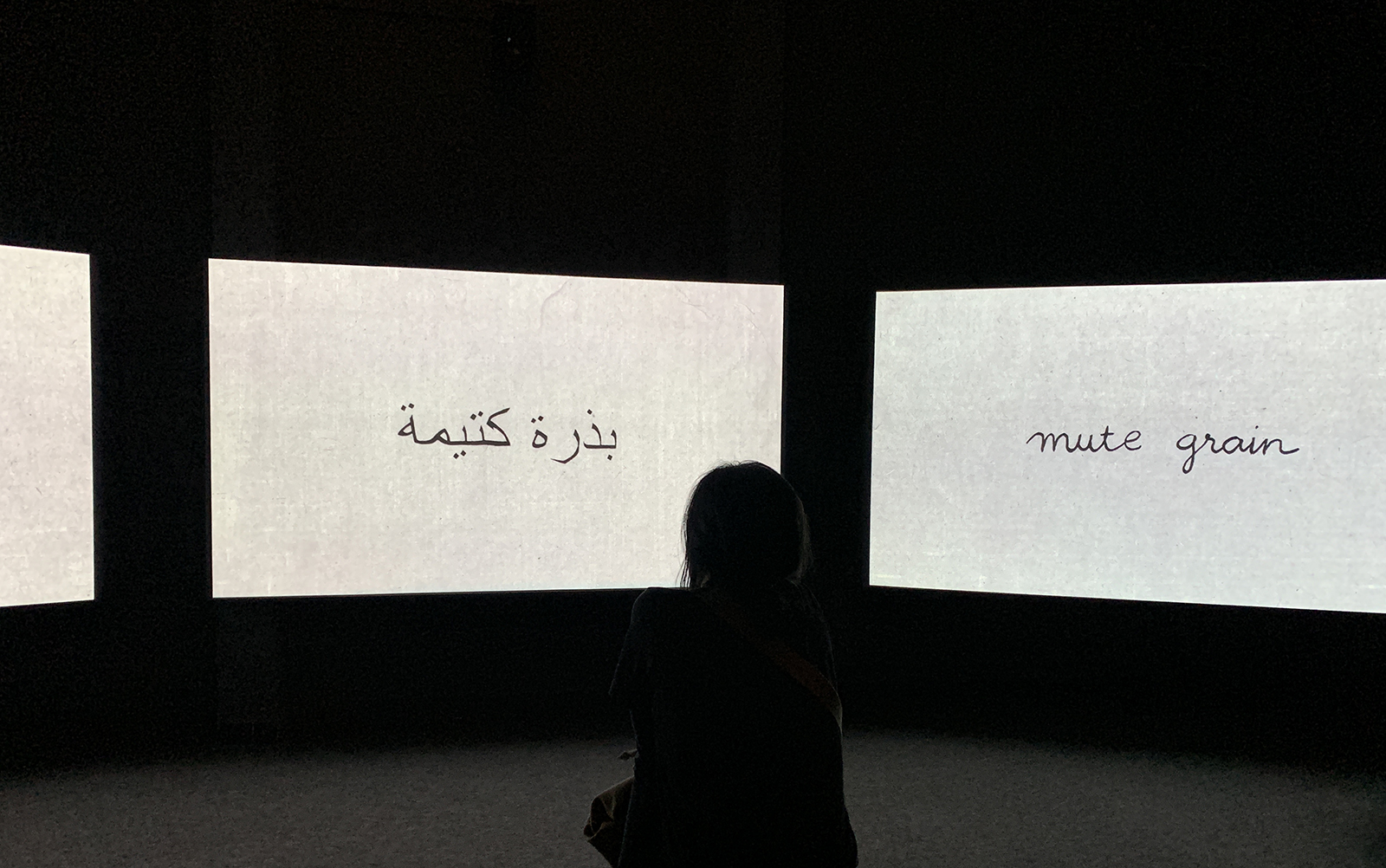

Mute Grain

2019

Three-channel video

15:45 mins, loop, black and white

Director of Photography: Le Vu Anh Huy

Producer: Truong Cong Tung

Music: Nhung Nguyen (Sound Awakener)

Commissioned by The Sharjah Art Foundation with additional support from the Rolex Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative

First installed at the 14th Sharjah Art Biennale, Leaving the Echo Chamber, 7 March - 10 June, 2019

The curious ardor one feels when feeling with the hand the naked flesh of rice, of soil, of oxen, of sheaves of corn.[1] My eyes and skin are Whitmanesquely infused with sensations of nearness as I watch Thao Nguyen Phan’s Mute Grain (2019), a filmic fable of longing and touching. Her fictional characters, fated to live and die in the historical famine that ravaged North Vietnam in 1945, are always caressing, rubbing, catching, picking, yearning for something with their hands.

The two protagonists, March and August, are named after the months of struggle and poverty in Vietnam’s agricultural calendar. They are adolescent siblings, left in a barren landscape from which the adults have eerily disappeared. Various storytellers in Mute Grain speak of how in 1945, under the French administration and Japanese occupation, thousands of civilians in Vietnam did not have enough rice to eat. The video is interspersed with constant streams of factual and fictive data surrounding the famine: archival photographs of frightfully emaciated children, fragments of oral interviews with survivors, phantasmal visions of rice grains being cruelly poured away into the flow of brutal histories.

The siblings, melancholically pretty and relentlessly bewildered with hunger, are often reaching for something with their cupped hands. Whether it is an insect, a pile of hay, a ripe jackfruit, or a precious bowl of white rice, their object of desire tends to only stay there for a second, then vanish into an inaccessible realm of fantasy. Peace and plenitude remain out of reach for the children, abandoned in times of famine. Nightmare strikes when August dies and becomes a famished ghost; her brother, March, ceaselessly walks around the deserted village, searching for her.

The two siblings can finally reunite in the place and time of myth. All around them, rice fields keep burning and soil drying; humans continue to die of hunger; uncoffined bodies wrapped in thin mats are seen rolling down the cold slopes of the dismal land. But in the impossible peace of a mythical cave, March is elated to find his sister’s wandering spirit, miraculously alive. For a short while, they share a bowl of sweet-scented rice. Soon August’s beautiful face fades away and March exits the mysterious womb of the cave to find out that three hundred years have passed.

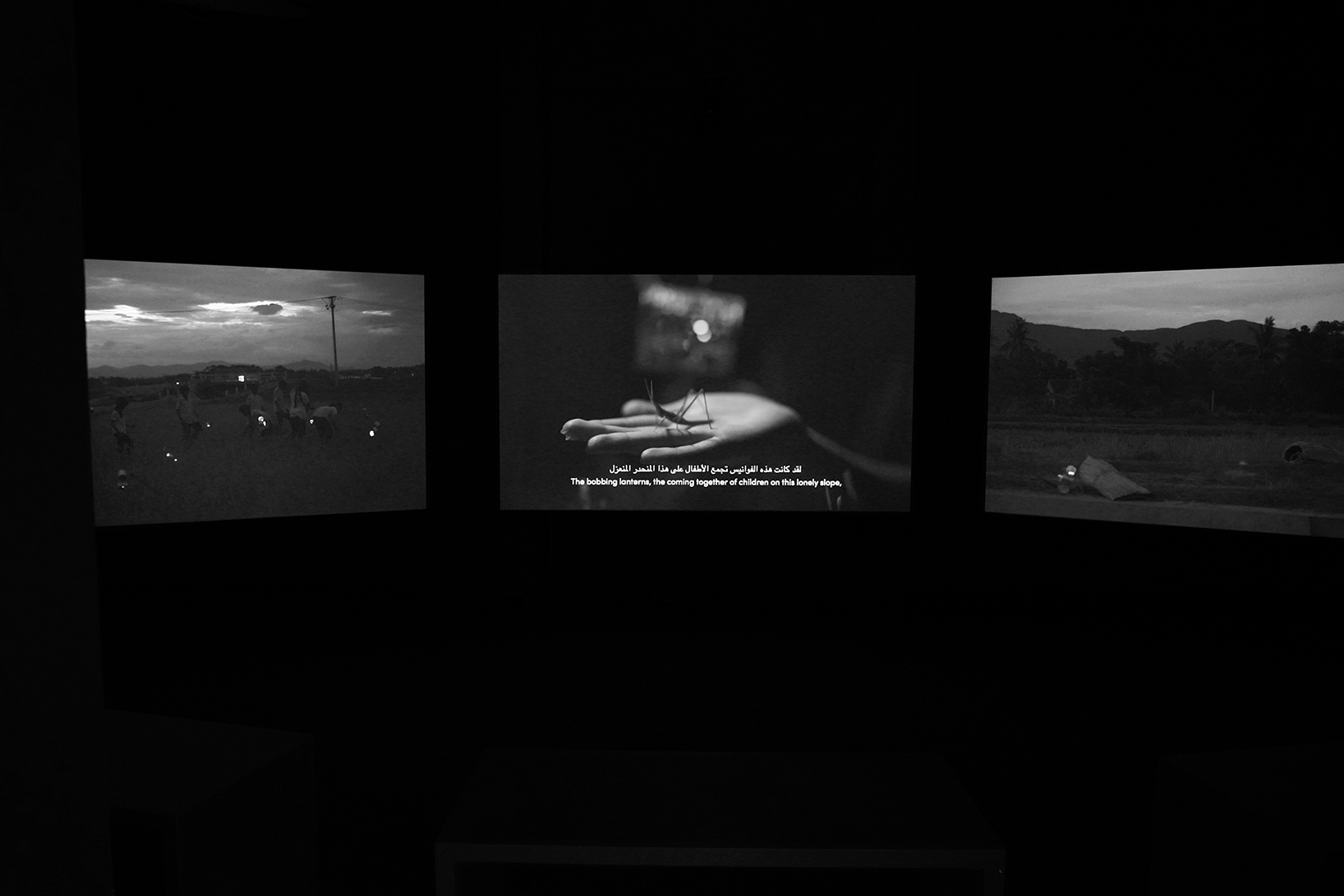

Like his sister, time has left him behind. Full of loss, full of sadness, he walks along the old river and joins a group of young children playing on the riverbank. Lovingly and carefully, they are making their own toy lanterns out of tin cans and little candles. Night arrives. The children keep on playing, forgetting the time as they search for crickets among the shrubs. In the dim light that emanates from the swiveling lanterns, August’s round cheeks, framed by her long black hair, magically re-emerge. March enters into yet another impossible dream as he comes near his sister. They stand face to face in the warm glow of glimmering candles.

Mute Grain’s final sequence turns into a mirage inspired by Yasunari Kawabata’s short story, “The Grasshopper and the Bell Cricket,” in which a young boy and a young girl experience an eternity of intimacy as they huddle over a bell cricket in the night, their small lanterns projecting their faint, tiny names onto each other’s kimono. Migrated to the gaunt, devastated landscape of a Vietnamese famine, Kawabata’s fairytale vision shines a heartachingly gentle and idyllic glow onto Thao Nguyen Phan’s two mythical characters, brought together again in a land far beyond the border separating the living and the dead. Their hands, no longer craving imagined nourishments, now delicately join in the shimmer of candles flickering like starlight.

In the time of play, of peace, of chimerical imagination and of fabled innocence, the lost sister is retrieved from the hauntings of the miserable famine, the hold of the solitary underworld. The blissful brother hands his sister a small brown cricket. Like the mid-autumn full moon of August, she releases a surge of laughter that soothes and entrances the world. The laughing joy that spreads on her face, then his face, supernaturally cancels the memories of starvation, desperation, suffering. Suddenly the terrible muteness of ruined grains and wounded lives passes gently into a smiling soundlessness that twinkles in the dark. This is the marvel of myth and it is just as Rabindranath Tagore once wrote: as tempest roams in the pathless sky, death is abroad and children play. On the shore of endless worlds, lost children meet again.[2]

[1] “feeling with the hand” from Walt Whitman, “Poem of the Body,” in Leaves of Grass (New York: Walt Whitman, 1856), 179.

[2] “tempest roams in the pathless sky […] death is abroad and children play”: Rabindranath Tagore, “On the Seashore,” 1912, in The Complete Poems of Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitenjali, trans. and ed. S. K. Paul (Delhi: Sarup & Sons, 2006), 254.

Text by Quyên Nguyễn-Hoàng